Words by: Rickey Gates

Photography by: Andy Cochrane

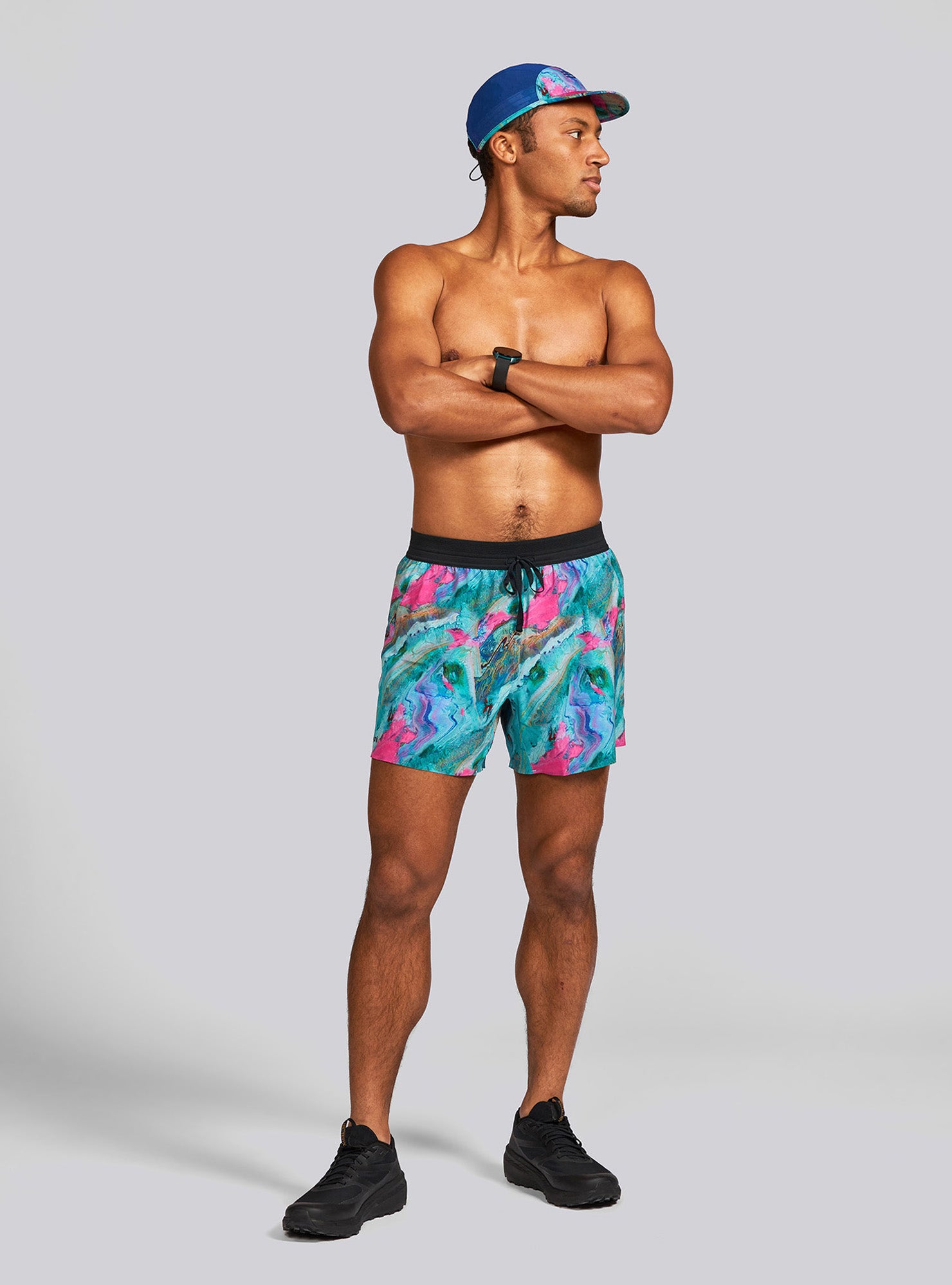

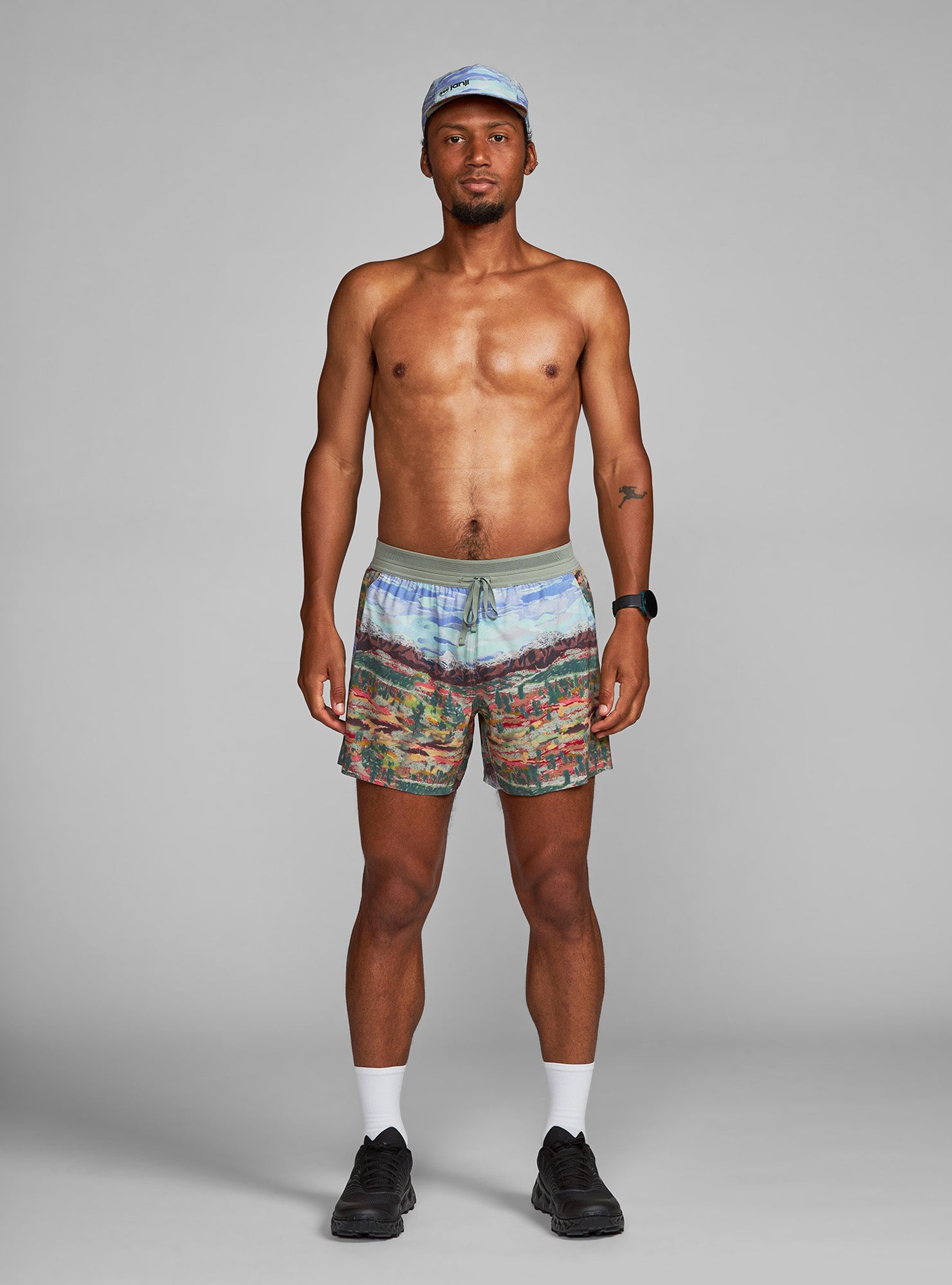

Packing List

“A trail is like a play,” Francisco said. “It needs a narrative."

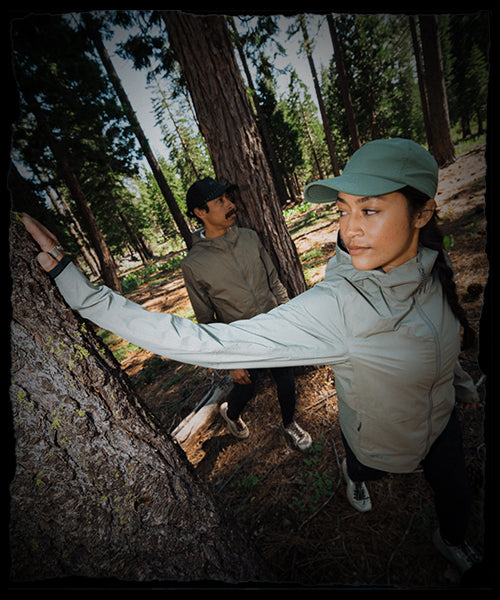

As we crossed the South Fork of the Toutle River, Andy announced that we were at the westernmost point of the Loowit Trail, which forms a loop around its namesake mountain, also known as Mount St. Helens. We're just getting to know each other and now I know that Andy spends an immense amount of time looking at maps, perhaps more than me. I ask if either of them know much about the spiritual practice of circumnavigating a mountain, to which they reveal that they know about as much as I do - that it's a thing, and that Mount Kailash, in Nepal, is the most famous example. I’ll later read that we at least circumnavigated it in the correct direction per Eastern tradition: clockwise, always keeping the mountain to our right - the clean side of our body and soul.

My companions are Ian McLellan and Andy Cochrane. The three of us running around Mount St. Helens together is further proof that no idea happens in a vacuum. We learned of each other just a few months prior, when a mutual friend informed us that we were essentially working on the same project - developing a list of 50 bucket list trails in the United States. Seeing how much prettier their spreadsheet was than mine, I decided that collaboration could only benefit the project. Over months of Zoom calls and WhatsApp group texts, we pooled our collective curiosity, opinions, and knowledge on each of the trails we were considering. The ongoing conversation has allowed us to agree on a magical 50 that we hope will paint a vast mural of the natural landscape this country has to offer.

One of the parameters - "Would you be comfortable convincing a friend to fly across the country for the experience that a trail can provide?" - was being put to the test on a hot summer day, circumnavigating a mountain with a plurality of names from the different cultures that she's touched over thousands of years of smoking, rumbling, and occasionally sitting quiet.

The story of Loowit as told by the Klikitat people is of love and jealousy and rivaling brothers - Wy’east and Pahto, or Mount Hood and Mount Adams. It's noteworthy that the characters are not just mountains, but volcanos. Across cultures and time, volcanoes are anthropomorphized into something more comprehensible to us. Perhaps because they quite literally breath and bleed. They grow and contract before our eyes within a timespan that geology doesn’t normally allow us to comprehend.

The sun climbed higher. We left the forest and entered the blast zone - simultaneously beautiful and hellish. Sturdy but immensely sparse vegetation scattered about the landscape revealed nature’s determination to live in almost any condition. Trees on nearby hillsides were still combed over from the explosive equivalent of 100 atom bombs. If I blur my eyes a little looking at the history books or my birth certificate, I was born on the day of the explosion. However, more accurately, I was born exactly one-year after the explosion but it seemed like a minor detail in my kinship with a birthday relative.

“Northernmost point” Andy said. We refilled waters in the ashen creek descending from the volcano’s collapsed north face. As the temperature rose, Ian’s cool, coastal adaptation betrayed him in the form of an uncooperative stomach. “I don’t want to be the stomach guy,” Ian said. “I’m never the stomach guy.”

On the north slope of Loowit , the three of us gazed up towards the summit at both what was there and what wasn’t there. The photo-montage of Smoking Mountain’s explosion 44-years ago reeled on repeat in my head. Ian, Andy, and I watched as the mountain exhaled palls of ash and cloud as a reminder that she is alive, breathing and ever present.

While the devastation caused by the eruption was staggering, one positive benefit was that an entire area around Loowit received designated protection. Because most of the previous trails became obliterated with the 1980 explosion, the subsequent trail design underwent a different process than most trails, which are utilitarian at their core.

“Most trails have a purpose rooted in history,” said Francisco Valenzuela, who was the recreation planner for the Mount St. Helens National Volcanic Monument when it was created in 1982. “A trail might have led to a cabin or lookout or it might have served as an old road or rail bed.” Given a clean slate, the trail designers for post-eruption Mount St. Helens were able to design the trails to tell a story or a narrative of the environment while also respecting sensitive habitats.

“A trail is like a play,” Francisco said. “It needs a narrative. We wanted to let nature do its own thing and not get in the way—which is a smart idea when it comes to volcanoes, because they do their thing no matter what.”

We continued our turn around the mountain, over Windy Pass and onto the Plains of Abraham. The intensity of the August sun and the haze of nearby forest fires intensified the feeling of passing through a terrestrial hellscape. Ian’s stomach did not improve but there was little to be done other than simply keep moving.

To run something, to exert oneself beyond comfort, to drink in the water flowing down the slopes, listen to the bird song and breathe in the intoxicating perfume of the flowers and pines… in short, to be entirely present with a place is to commune with something bigger, older, and wiser than any of us individually.

The symmetry of the trail, when starting from the south side of the mountain, brought us back into the trees after nearly 15 miles of total exposure. Shortly after, we slowed to a crawl as we passed through a strewn lava field that mimicked the one we had crossed several hours earlier, as the first light of the sun was igniting the atmosphere. Rejoining the popular summit route, we descended the final couple of miles back to the car with weary and ashen summit seekers. We quietly guessed who had made it and who hadn’t based upon folks’ current disposition.

Trail History

Mount St. Helens is the youngest of the volcanos in the Cascade Range that spans Oregon, Washington, and Northern California. Volcanic uplift started just over 40,000 years ago, which, in geological time is the blink of an eye. Indigenous communities that have called the area home date back several thousand years and across many cultures. For the Klikitat people, Loowit has long been a central figure in their creation stories.

European settlers moved into the area beginning in the early 1800’s preceded by several explorers including Captain George Vancouver who renamed Loowit as "Mount St. Helens" to honor a friend and nobleman Baron St. Helens of England. Not only did St. Helens never lay eyes on the mountain, he never set foot on North American soil.

Smoking Mountain is still active to this day. The most recent eruption occurred just a few years back, from 2004-2008.

Getting There

Mount St. Helens is located in southwest Washington just an hour north of Portland, Oregon and a couple of hours south of Seattle.

Simple car camping at the Bivouac Camp will help you get on the trail early in the morning with fellow hikers seeking out a summit. There are pit toilets but no water.

On the Day

Get an early start - especially in the summer time. Temperatures can approach 100 degrees with little to no shade for a majority of the run. Lava fields parenthetically greet you early on and late in the loop regardless of the direction chosen. You can count on your pace slowing significantly going through these boulder-strewn fields. Stash extra water in your car as there is no water to be had at the parking lot.

Run with Rickey

Feeling inspired? Sign up to join Rickey on his next big trail-running trip.

About Rickey

For the past thirty years, running has been a central part of Rickey Gates’s life. Whether it be in the competitive realm of racing or the obsessive realm of curiosity, or a mindful space of meditation, running has long been the primary medium through which Rickey has interacted with the broader environment around him.

In an effort to understand his country, community, and self, Rickey completed two unbelievably ambitious, back-to-back running projects: TransAmericana (2017) in which he ran across the entire United States, and Every Single Street (2018) in which he ran, street by street, the entirety of San Francisco. His current obsession (which you are currently reading) is to paint a picture of North America through trails. He lives in Santa Fe with his wife and two children.