Words by: Rickey Gates

Photography by: Ian MacLellan

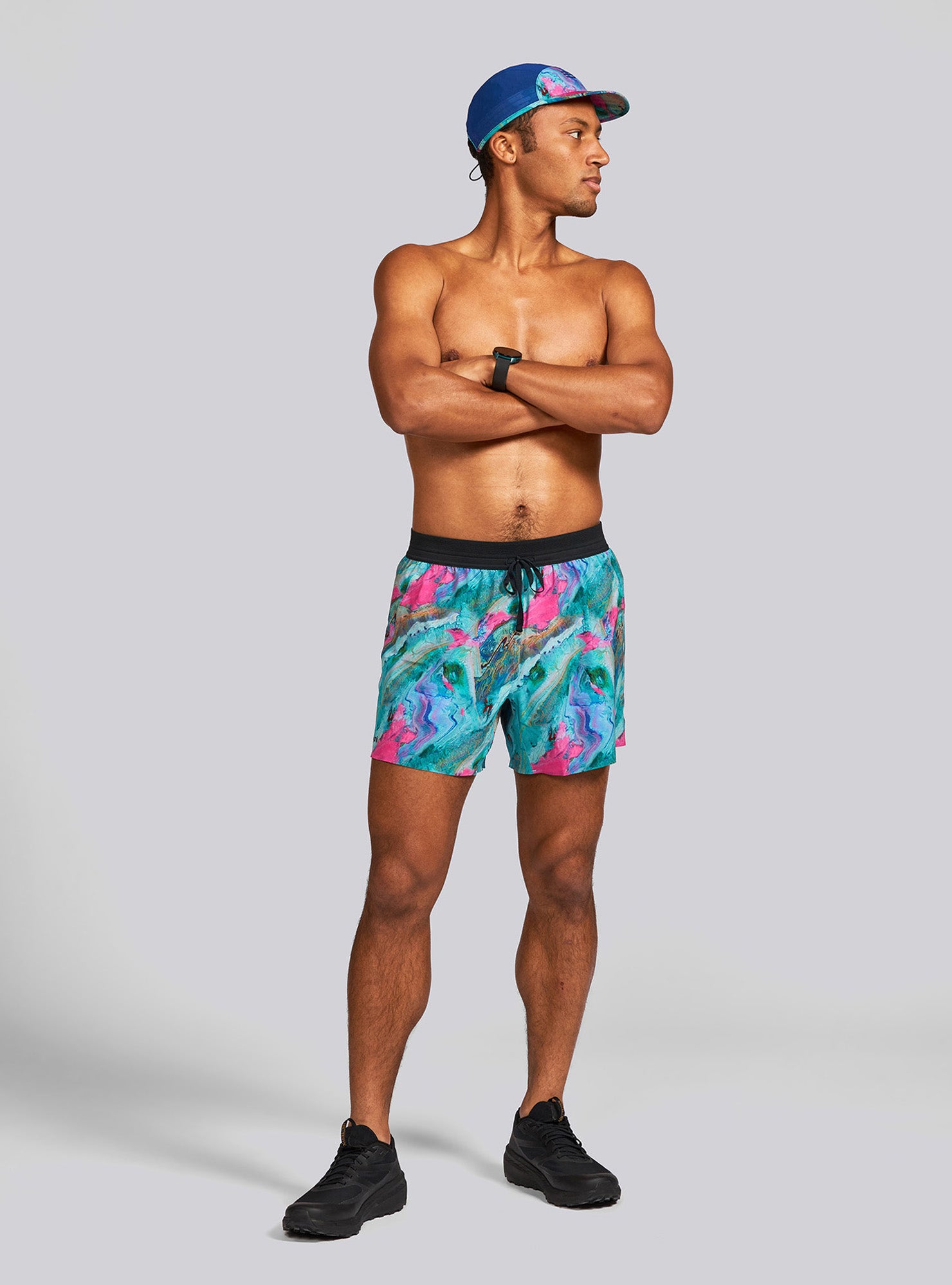

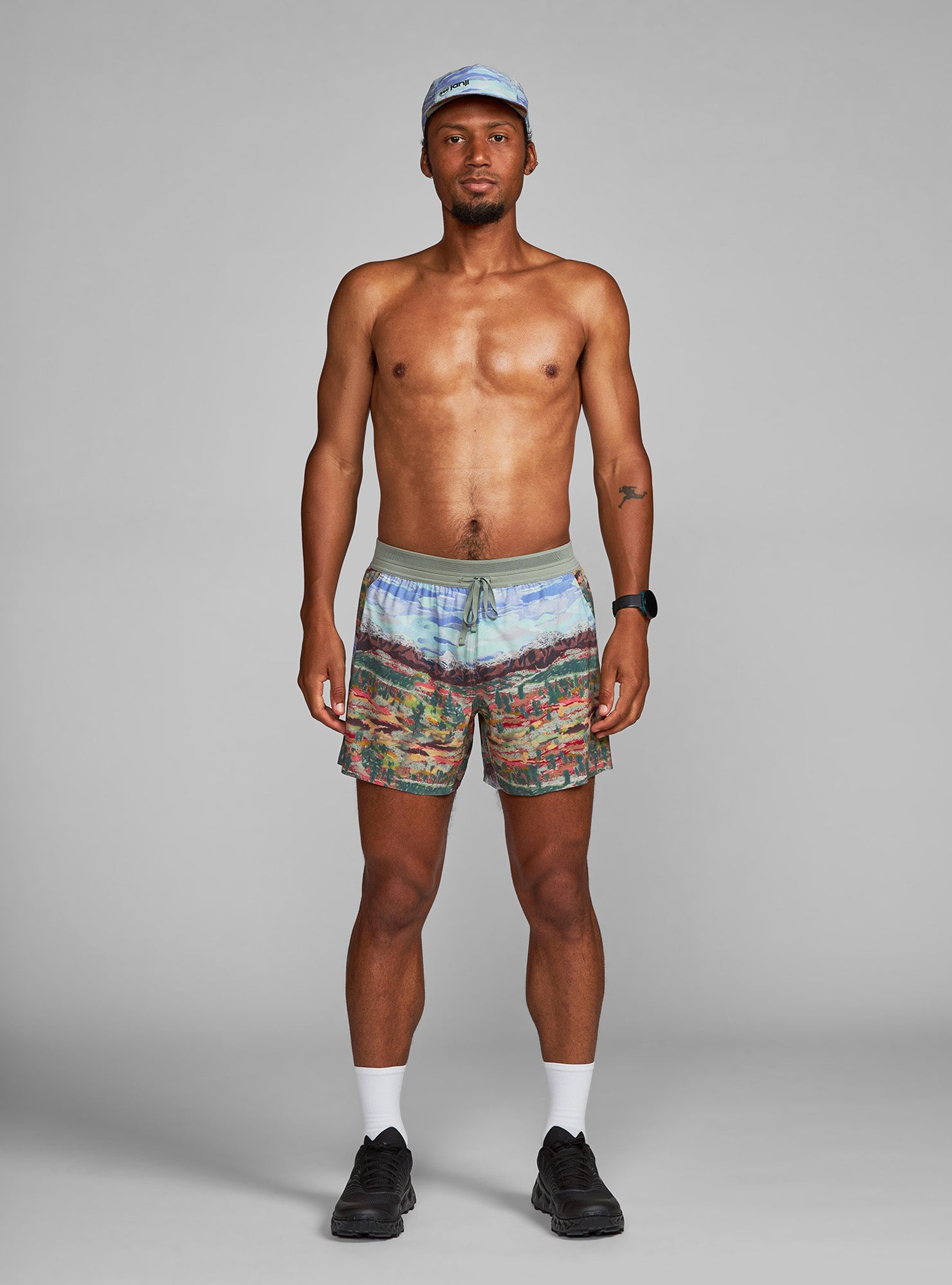

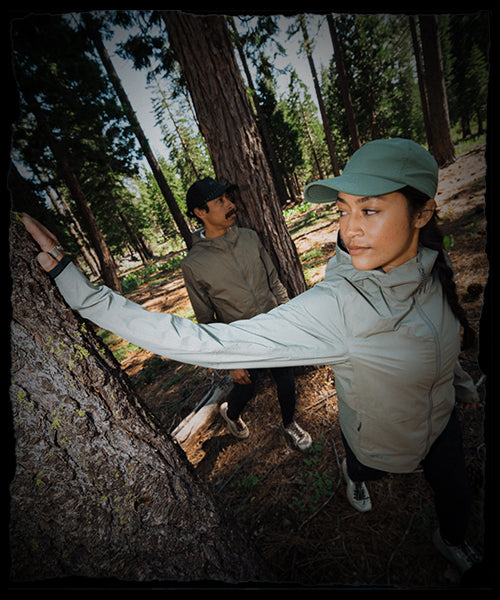

Packing List

Historically, the fall-line trails that make up The Pemi come from a different era of trail building - meant strictly for hikers.

The clouds were still glowing with the warmth of the early morning light as we crested Bond Cliff - the first of eight 4,000’ peaks that make up the contour of the Pemigewasset loop (better known, quite simply, as The Pemi) in the White Mountains of central New Hampshire. After several thousand feet of climbing up a rocky and rooted trail we were at once atop the white granite ridge with an inspiring and humbling view of the day’s immensity ahead.

It is a rare opportunity to physically observe the entirety (or near entirety) of a full day’s effort. So, on the cliff, above the trees, I gazed north and west across the valley where the summits of Lafayette, Flume and Liberty - all peaks we’d be going up and over as the day moved on - sat calm, waiting for us. Between us and those peaks rested Owl’s Head - a humble mountain that splits the entire basin into two drainages. Without much effort, one can easily imagine the glaciers that carved out and around Owl’s Head to create this perfect crown of mountains.

The trail was described to me quite simply as a “classic” - a word that gets thrown around in every circle from cars to music and from books to mountaineering routes. I’ve had a hard time putting an exact definition on what I think it means for a trail to be a “classic” other than when I’m running one of those trails the feeling is sublime. History of the area, cohesiveness and difficulty of the trail, uniqueness of ecology and geology - all play a part in securing the collective attention of runners and hikers to pursue a given route repeatedly, year after year. For the Pemi, a glance at a map would suggest a similar route - trails aside. Ultimately, it is the feeling that the trail gives us that provides the enduring quality that it needs to be a Classic.

I was tagging along on a couple of friends’ semi-annual run around the Pemi. Mike Burnstein, co-founder of Janji and his friend Chernet Anbessa have amassed several Pemi loops over recent years. They know the route well enough to know that they are making good time, but also that they will still be hobbling along eight hours from now. The Pemi, it seems, always catches up with you. My running pack contained $20 worth of junk food that I had quickly gathered at a Dollar General the evening prior - gummies, jerky, jumbo Donetts, a sweet and salty party mix and a dozen Hi-Chews to help me get through the final miles.

We continued north to Mount Bond, in a counter-clockwise direction around the loop, beneath a canopy of birdsong - sparrows, thrushes and warblers. Shortly after the summit, the Appalachian Trail joins the Pemi Loop where the chance to see an elusive thru-hiker, if spotted, will certainly inspire, if nothing else.

The Appalachian Mountains express themselves differently as small changes are made in latitude, elevation, geology and the ecology that follows, not to mention the user interface that governs the experience mainly in the form of a trail - an immensely rugged trail. Several trips to New England over the past several years have instilled in me a respect for the diminutive mountains of the Northeast with their rounded, tree covered mountain tops and humble elevations, if for no other reason than the trails demand it.

Historically, the fall-line trails that make up The Pemi come from a different era of trail building - meant strictly for hikers. Unlike most trails out West that were cut by teams of horses thereby limiting the steepness of a given trail to a casual 5%, New England trails, for many reasons, embrace a more direct approach. Sturdy geological features also count for something when it comes to the resilience of these weather-beaten paths - beneath the carpet of underbrush and duff is generally solid rock. So, what little erosion occurs as a result of rain and human traffic does little to the trail following the loss of that topsoil.

Galehead Hut

We arrived at Galehead Hut and treated ourselves to coffee and a snack. We swapped info on trail conditions with folks coming from the opposite direction and vice versa. The exchange of information is really just an extension of greetings and small talk as it seems that little extends beyond “that way - the trail is steep and rocky”. After finishing our coffees, filling water bottles and using the toilet (leave no trace!) we continued on and up to Mt. Garfield - generally considered the half-way point of the loop.

My mind can’t help but wander to the Fastest Known Times posted on this trail over the years. The record has changed hands many times, but one name stands out in particular, in large part for his complimentary feats around the US and beyond. Though Jack Kuenzle’s time on the Pemi no longer stands as the FKT, his times on technically demanding routes such as Mont Blanc, Mount Rainier, the Presidential Traverse and the Devil’s Path suggest that technical prowess is essential for moving quickly through this terrain (and the willingness to pee your pants per Kuenzle’s run report).

Mount Lafayette

We moved up and over Mount Lafayette, the high point of the trail, glancing over to our left at Mount Bond and Bond Cliff across the vast valley where sunrise had greeted us several hours prior. The morning birdsong of sparrows, thrushes and warblers quieted to make room for the sporadic trill of the dark-eyed junco, flittering about the trees, curiously keeping pace with us. Going counter-clockwise, the trail following Mount Lafayette is a consistent downward trajectory back down to the East Branch of the Pemigewassete River. Though not inconsequential, the summits of Haystack, Liberty and Flume seem to exist as mere viewpoints in comparison to their predecessors from earlier in the day.

The remains of the railroad bed at the base of the mountain welcomed us back to the valley floor, simultaneously reminding us of a by-gone era of gratuitous lumber harvesting. We jogged the final couple miles back to the Lincoln Woods Trailhead where a river pool helped wash away 32 miles of mud and sweat.

The Pemi in a day, I thought. Classic, indeed.

Trail History

There is no question that the Pemi enjoys much of its enduring popularity thanks to the number of 4,000’ peaks that can be consecutively summited (with four additional out-and-back summits from the loop if one has the extra stamina). Much like the 14,000’ peaks (Fourteeners) of Colorado, the height of the peaks brings both hikers and runners together for a cohesive and compelling challenge on their way to tagging the 48 4,000’ers of New Hampshire and/or the 67 of New England.

Before the Pemigewasset became a destination for hikers and runners in New Hampshire’s largest wilderness area), it experienced sixty-plus years of unchecked logging at the hands of J.E. Henry’s lumber operation based out of neighboring Lincoln, NH. In total, Henry laid over 60-miles of standard and narrow gauge railroad throughout the region to harvest the local forests. Not much for conservation, Henry once boldly proclaimed “I never see the tree yit that didn’t mean a damned sight more to me goin’ under the saw than it did standin’ on a mountain.”

The period prior to the logging era of the White Mountains followed a similar story line as much of the Appalachians from the 17th to mid-19th centuries. First came the explorers, then the trappers, then small scale farm and agriculture concurrent with the forced removal of the indigenous population which, in the White Mountains of New Hampshire was the Abenaki - a linguistic sub-group of the widespread Algonquian-speaking people that were spread across much of modern day eastern and central Canada as well as the Great Lakes and coastal New England. The Indian Removal Act forced the few remaining indigenous tribes of the White Mountains north and west to Quebec and elsewhere.

Though the geological story of the Appalachian Mountains is rather complicated, a very brief overview of the White Mountains can be summed up with two outstanding events - the first occurred 100 million years ago when the North American Plate glided over a mantle plume or “hot spot” of magma. A weakness in the plate allowed for a magma intrusion thus creating the entirety of the white granite ubiquitous across the White Mountains. The second event occurred much more recently - 80,000 years ago up until 10,000 years ago when glaciers carved U shapes throughout the valleys.

Getting There

The start and finish for the Pemi loop is at the Lincoln Woods Trailhead - a modern, paved parking lot with toilets, potable water and a park-and-pay kiosk. Conveniently located just across the highway is Hancock Campground where you can count on getting some sleep if driving in the night before. Just a few miles away is Lincoln, NH bustling with lodging, commerce and food.

On the Day

Check weather conditions! While you might get lucky with the same weather we had, you might also get unlucky with some of the weather that the White Mountains are infamous for. At the neighboring summit of Mount Washington, a world record wind was recorded at 231mph. While you might not experience that level of wind, you can be assured that White Mountain weather is nothing to be reckoned with.

Clockwise vs. Counterclockwise: Most folks seem to prefer to do the loop in a clockwise direction which heads directly up Mount Flume after just two miles on the old railroad bed. Going this direction, you’ll descend from Bond Cliff back to the railroad bed that will take you back to the parking lot over the next five miles. We preferred to do those five miles at the start, in the dark, and be closer to the end once off of Mount Flume. Six one, half dozen the other, as they say.

As is common with ridgetop running, once above the valley floor, there is very little water to be found. Seasonal streams can sometimes be running directly down the trail while at other times, be bone dry. Camel-up at Galehead Hut. Treat yourself to a coffee and a pastry. Once back at the parking lot, soak in the East Branch of the Pemigewassete River just downriver of the pedestrian bridge.

Run with Rickey

Feeling inspired? Sign up to join Rickey on his next big trail-running trip.

About Rickey

For the past thirty years, running has been a central part of Rickey Gates’s life. Whether it be in the competitive realm of racing or the obsessive realm of curiosity, or a mindful space of meditation, running has long been the primary medium through which Rickey has interacted with the broader environment around him.

In an effort to understand his country, community, and self, Rickey completed two unbelievably ambitious, back-to-back running projects: TransAmericana (2017) in which he ran across the entire United States, and Every Single Street (2018) in which he ran, street by street, the entirety of San Francisco. His current obsession (which you are currently reading) is to paint a picture of North America through trails. He lives in Santa Fe with his wife and two children.